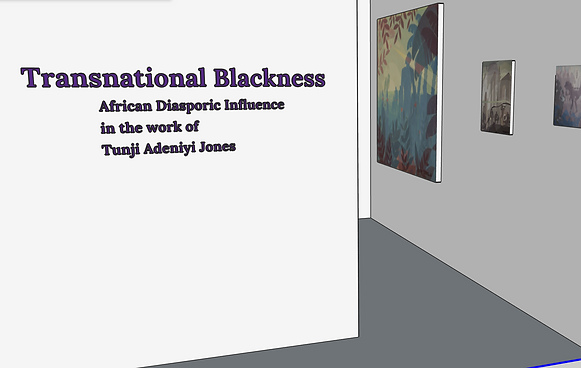

Transnational Blackness

African Diasporic Influence in the work of Tunji Adeniyi Jones

Neil Grasty

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones’ practice has a distinctly transnational quality. The transnational quality of his practice is informed by his experiences studying and working within the United Kingdom, United States, and Senegal. Transnational Blackness: African Diasporic Influence in the work of Tunji Adeniyi Jones traces this quality of his work through two of his influences, Aaron Douglas, and Ben Enwonwu. Both artists are prominent figures in the Modernist movements of their respective regions of the African diaspora. Like Jones’ both artists’ work has a certain transnational quality. By exploring these influences, the exhibition aims to position the transnational quality of Jones’ practice as being uniquely African diasporic. Transnational Blackness argues Jones’ practice as embodying a transnational Blackness by putting his practice in conversation with Douglas and Enwonwu, as well as highlighting the transnational quality of their practices.

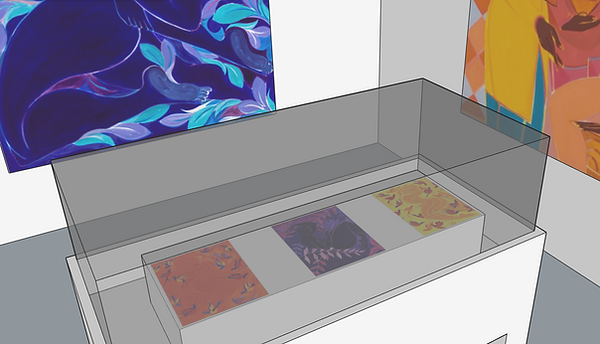

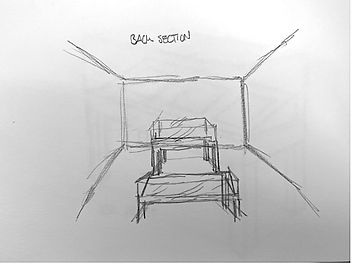

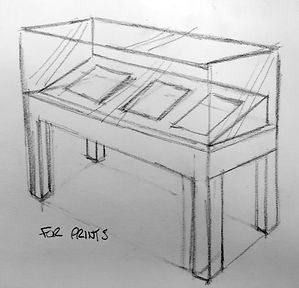

The layout of the exhibition addresses these themes by putting Jones’s work in direct dialogue with the practices of Douglas and Enwownu. The front room featured in the layout sketch includes work by all the artists, the right wall features work by Douglas, the left by Enwownu, the back center wall features only Jones’s work, and the front center wall features one work by each artist. This placement is meant to orient visitors in the practice of each artist and their connections. The back room solely features paintings and printings by Jones. Visitors are meant to go to the front room first to understand the influence of Douglas and Enwonwu on the work of Jones, then just see his work in the back room. Custom viewing cases will be commissioned for the back room for prints by Jones. On the following pages images of the layout are featured as well as a tentative checklist of art works featured in the exhibition.

Aaron Douglas

(African American, born 1899 Topeka, Kansas, USA – died 1979 Nashville, Tennessee)

Aaron Douglas was a painter who was mainly known for his work during the New Negro Movement (now referred to as the Harlem Renaissance). He earned his BFA from University of Nebraska Lincoln in 1922.[1] After working as a High School art teacher in Kansas City, Missouri for two years he moved to Harlem, NYC. At the time Harlem was heralded as the “Mecca of the New Negro”[2] due to its lively African American cultural and artistic scene. In Harlem, he studied under the German immigrant Winold Reiss, who helped him develop his distinct style. Douglas’s style is marked by his incorporation of Cubism, Art Deco, and African imagery. His work was inspired by African American thinkers of the period such as Alain Leroy Locke. Douglas’s work illustrates Locke’s idea of the Ancestral Arts which encouraged Black artists of the period to look to African art for inspiration.[3] Douglas would go on to obtain an MA from Columbia University’s Teachers College in 1944. After the Harlem Renaissance he continued working as an artist and taught at Fisk University until his retirement in 1966.[4]

Ben Enwonwu

(Nigerian, born 1917, Onitsha, Anambra, Nigeria -died 1994 Lagos, Nigeria)

Ben Enwonwu was a painter and sculptor of Igbo origin. His father was a traditional Igbo sculptor which greatly informed his practice and artistic philosophies. He engaged Igbo artistic ideals such as Agwu, Ime Mmanwu, and Dinka.[5] His formal training art began at the British Colonial administered Government College of Umuahia, Nigeria. He studied under the British art professor Kenneth C. Murray. Later he would go on to study in the UK, he obtained a scholarship to study at Goldsmith’s College in London in 1944, and then studied at Oxford University’s Ruskin School of Art until 1948. He would later return to Nigeria in 1948, and work between the UK and Nigeria for the next decade. He is known for his immense impact on Nigerian/African modern art, and for his international acclaim. He exhibited extensively in the UK and was even commissioned to create a sculpture of Queen Elizabeth in 1955 for the Parliament Buildings in Lagos.[6] He would also be named“Africa’s Greatest Artist” by the African American magazine Ebony. After Nigeria’s independence in 1960 he would receive sculpture commissions for various public buildings. Within the colonial and postcolonial period especially, Enwonwu’s work would help shape national identity through the implementation of indigenous and western aesthetics in his work.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

(British-Nigerian, Born 1992 London, UK)

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones is a British-Nigerian painter and printmaker working in Brooklyn, NY. He was born in 1992 in London, England to Yoruba parents. He received his BFA in 2014 from Oxford University’s Ruskin School of Art and his MFA in printmaking and painting from Yale School of Art in 2017. His work is deeply influenced by his identity. This influence was catalyzed by a 2012 trip to Nigeria; here he was encouraged to draw from his unique position as a British-Nigerian. He became influenced by Nigerian artists such as Ben Enwonwu. Homage to his heritage is seen through the incorporation of

West African mythology and iconography in his work.

West African iconography is presented through motifs such as masks as well as through the lines adorning many of his figures. The lines adorning his figures are meant to be reminiscent of bodily scarification processes within many African tribes. He utilizes these myths and iconographies to highlight the overlooked histories of West Africa. Upon arriving to Yale School of art he was exposed to African American figurative painters such as Aaron Douglas, Bob Thompson, and Kerry James Marshall. Influence of these various African Diasporic artists is evident in Adeniyi-Jones, lively palettes, and distinctly figurative works. His figures have characteristically curved forms and dancerly poses. He thinks of dance as a universal form of communication that transcends language barriers. Through his work he aims to depict a diasporic Black body rather than one representative of a specific locale. In addition to his African diasporic influences, he draws from the two dimensionality of Modernist abstractions styles such as Cubism.

Transnational Blackness

Within the exhibition Blackness is understood as being of African descent. Throughout the exhibition Blackness is illustrated through the identities of the artists and aesthetics of the work. Furthermore, the exhibition understands being transnational through its common definition, the Merriam Webster dictionary defines it as “extending or going beyond national boundaries”.[7] The exhibition also engages this idea through a 2021 Cultured magazine article on Jones’s work titled “Tunji Adeniyi-Jones Paints a Turbulent Dance with Identity”. Within this article he alludes to his work engaging a kind of transnational Blackness, he states:

“When I started a bit back, I was definitely trying to say that these are Yoruba-inspired characters, but now I want [the interpretation] to be more open and accessible. I feel like I’m trying to paint a figure now that is more versatile culturally, so it’s not specifically a West African figure. It could be a Black American, Black European or someone from anywhere else.”[8]

Later in the article he also aligns his with this ideal when recounting his time in the United States he says:

“There’s a very specific kind of Blackness in this country that has affected everything that’s happening [in my paintings]. The work got hypercharged by that self-definition I was speaking to as well. It’s benefited from me attaching myself to an expansive kind of history of the Black experience.”[9]

These two excerpts have helped ground the thesis of the exhibition. To further understand the idea of transnational Blackness I examine this quality in Jones’s work and its presence within two of his influences Aaron Douglas and Ben Enwonwu.

Douglas’s work has a transnational quality due to its mixing of Modernist European traditions and his homage to African artistic forms. This homage to African art is linked to thinkers of the time such as Alain Locke. Locke coined the artistic philosophy of the Ancestral Arts which encouraged African American artists of the period to look to African art for inspiration.[10] The transnational quality of Douglas’s work is deepened by his consistent depiction of African American life and the diasporic experience at large. A prime example of this may be seen in his Aspects of Negro life Series. The transnational quality of Douglas’s practice is positioned within Afro-America, Africa, and Europe.

Similarly, Ben Enwonwu works in European artistic styles yet manages to insert his Nigerian/Igbo identity into his work. Enwonwu was celebrated by the British Colonial regime for his artistic abilities[11] which afforded him opportunities to study art and exhibit in the UK. Nonetheless, he was intentional about creating work that encompassed his Nigerian/Igbo identity within the aesthetic qualities and artistic philosophies of his work.[12] This would define the transnational quality of his work since it was in dialogue with European artistic traditions and his African heritage. This quality is even more nuanced since he worked during both the colonial and postcolonial period of Nigeria. His artistic practice during these periods helped him shape national identity which became a facet of his work’s transnational quality.

Like both artists, Jones’s work embodies a transnational quality, particularly a transnational Blackness as argued in the exhibition. Jones’s drawing from diasporic artists such as Douglas and Enwownu inform the transnational quality of his work. This is especially true since both artists have been historicized as being representative of their respective diasporic cultural identities. Jones melds the aesthetics of their identities within his practice.

Additionally, his professional and academic experiences in places such as the United State, Senegal, and the United Kingdom define the transnational quality of his work. This is especially true when one considers his work being exhibited in the US and UK, Jones’ career, and practice positions itself as being transnational. Lastly, his identity as a British-Nigerian living and working in Brooklyn, NY make him a transnational figure.

Conclusion

Overall, my exhibition aims to highlight the career of the contemporary artist of Tunji Adeniyi-Jones as well as put his work in dialogue with historical African diasporic artists. The transnationality and Blackness within Jones’s work will be emphasized through the work of Aaron Douglas and Ben Enwonwu. In addition to Jones’s practice the exhibition highlights African Diasporic Modernisms. Douglas’s and Enwonwu’s practices are often noted as being quintessential to the Modernist art movements within their respective regions of the African Diaspora. Unfortunately, their practices and African diasporic Modernist art movements haven’t been largely acknowledged in traditional art historical canons. My exhibition aims to address this and other issues within art historical canons.

Notes

1. Nancy Anderson, “Aaron Douglas,” Artist Info (National Gallery of Art, September 29, 2016), https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.38654.html

2. Survey Associates, “The Survey Graphic, March 1, 1925. (Volume 53, Issue 11),” University of Minnesota, accessed November 8, 2022, https://umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll336:2133

3. Alain LeRoy Locke, “The Legacy of The Ancestral Arts,” in The New Negro: An Interpretation (New York: A. and C. Boni, 1925): 255-261.

4. Nancy Anderson, “Aaron Douglas”

5. Sylvester O. Ogbechie, “Ben Enwonuwu: Aesthetics and Artistic Identity in Modern Nigerian Art,” Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 16-17 (January 2002): pp. 24-31, https://doi.org/10.1215/10757163-16-17-1-24, 26: 28.

6. Hannah O'Leary, “BEN EWONWU MBE,” in African Artists from 1882 to Now (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2021):106.

7. “Transnational Definition & Meaning,” Merriam-Webster https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/transnational

8. Enuma Okoro, “Tunji Adeniyi-Jones Paints a Turbulent Dance with Identity,” Cutlured Mag (Cultured Magazine, September 20, 2021), https://www.culturedmag.com/article/2021/09/20/tunji-adeniyi-jones

9. Ibid.

10. Alain LeRoy Locke, “The Legacy of The Ancestral Arts,” pp. 255-261.

11. Sylvester O. Ogbechie, “Ben Enwonuwu,” 26.

12. Sylvester O. Ogbechie, “Ben Enwonuwu,” 28.

Neil Grasty is an Art History major, Curatorial Studies and French double minor at Morehouse College. He has been a member of the Atlanta University Center Art History + Curatorial Studies Collective since his inclusion in the first Early College Program summer session in 2019. He is currently a UNCF / Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow.